My mother’s 89th birthday is next month. The celebration will be simple, perhaps bake her a cherry pie, take her to lunch at one of her favorite places, and give her something she needs like new pajamas. She no longer requires a party she won’t comprehend.

Mom’s world now is a small apartment in an assisted living facility. When we set up her place, we placed photos of family members on walls and end tables, but she doesn’t remember the names of those she loves. Occasionally she may point at one and ask, “Now who’s this?” Dementia has clouded her mind and slowed her body. This once determined woman sleeps most of the day. Conversation is stilted and awkward. Her good days are a welcome surprise, but often she’s quiet. Sometimes she will ask about my husband Rock, but during my visit last week, she was lost in a muddled fog.

When I look into Mom’s bewildered face, I attempt to recount who she used to be. Not only was she our mother, but she was creative, athletic, opinionated, competitive, biting, and smart.

Sally Jo Warner was born in Burlington, Wisconsin, on August 13, 1935. The youngest of six, she was outgoing throughout her school years. She was a cheerleader, an actress in summer stock theater, and a part-time associate at an upscale dress shop. Yet, loss entered her life early. Her father Charles died when Mom was sixteen, her oldest sister Betty died a few years later, and one of her good friends died in a car accident while on a double date with Mom and two boys. Tragedy imprinted her young life.

Hoping to escape her pain, Mom moved down to Decatur, Illinois, to attend Millikin University, but love interrupted her plans. She and Dad wed on June 14,1957, and seventeen months later I was born, followed by brother Jeff, sister Ann, and youngest brother Bruce. Grief followed her, though, when her mother, my Nana, died in 1968.

Mom taught swimming and lifesaving courses, often dragging us to pools around town while she worked. Even today when I catch a whiff of chlorine, I’m whisked back to the YWCA pool where she would enroll all of us in swimming lessons while she taught her students CPR. Much of my childhood was spent in locker rooms, surrounded by older women in stages of undress.

She was also my Girl Scout leader for a few years. Along with crafts and troop meetings, I remember her choreographing a dance we would perform for parents. It was to “Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head,’ and we all had umbrellas as our partners. She wouldn’t let me be in front because she said she didn’t want to be accused of nepotism. I was so angry with her, but now I realize I just wasn’t a good dancer and she didn’t want me to ruin the show.

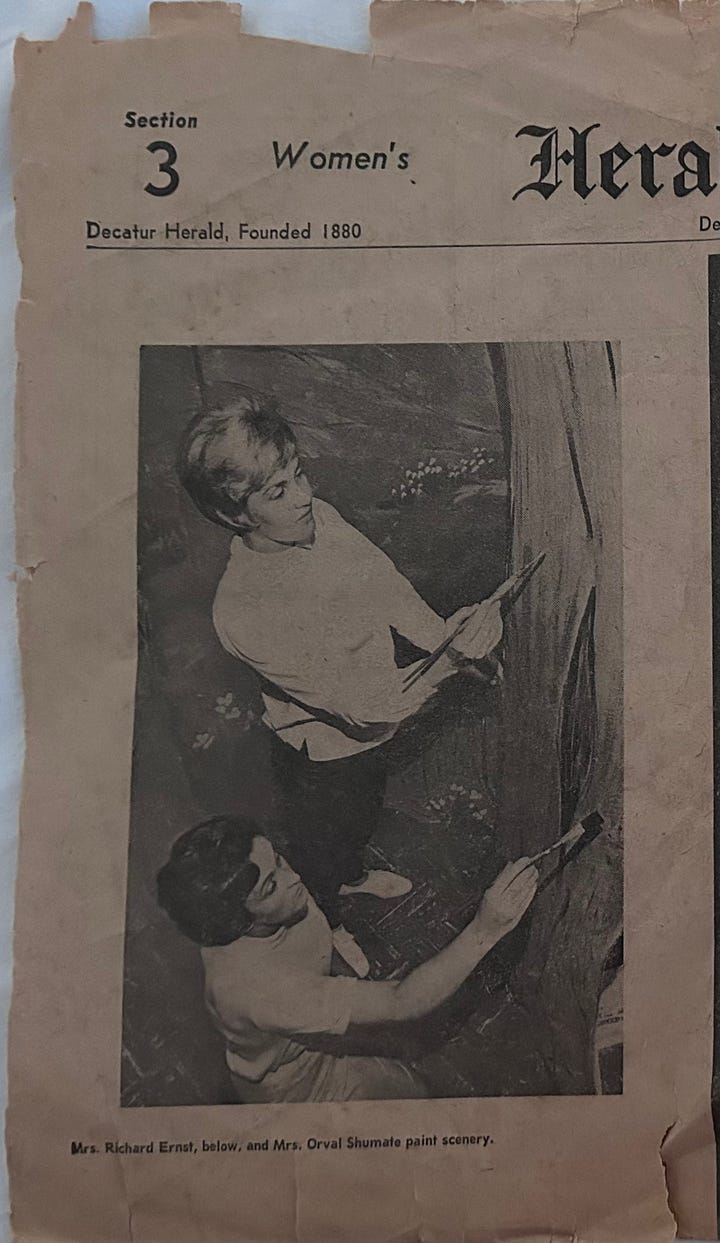

Sewing, knitting, and painting were Mom’s creative outlets. I proudly wore her double-knit creations to school. She knit sweaters, baby blankets, mittens, and slippers. Her painted flowers graced Christmas ornaments, a few of which I put on our tree every December. One of my biggest regrets is donating all the sweaters she knit the boys. How careless I was back then, tossing aside memories.

Mom was the first of the mothers to go to work. She spent most of her career as a principal’s secretary, first at Woodrow Willson Junior High where I attended. I can still feel the rush of humiliation when she pulled me out of band to reprimand me for getting a low grade on a math test. Mom, though, ran the office with a ferocious hand. No foolishness or talking back on her watch. My friends thought she was scary, and I just replied, “You haven’t seen her at home!”

The four of us had chores on Saturday mornings: cleaning bathrooms, vacuuming, wiping up the kitchen, and even raking the blue shag carpet that graced our living and sun rooms. Groovy. If we ever told Mom we were bored, there was a list of things we could do around the house.

Mom was a voracious reader. She always had a book in her hand, and would often retreat up to her bedroom to read. Dad would complain, “Your mother hides in that room with her books,” but with four boisterous and argumentative children, I realize now it was her escape into other worlds of romance and intrigue. Who can blame her?

Along with swimming, Mom also played a mean game of tennis. Competitive to the core, she insisted on playing with others on her level, which meant I wouldn’t be invited to the court. My brother Bruce, on the other hand, could match her swing for swing. Later, when she got older, she traded in her racket for golf clubs and loved playing the 9-hole courses in town with her friends.

So, when I get melancholy over how my mother is now, I attempt to recall the picture I have in my head of a mother who rarely stopped, except to read. A woman who bossed everyone around, even my father from time to time. Not a cuddly mother, but one who loved us all with a fierceness no one wanted to cross. Someone who never really came to terms with the loss in her life, but instead masked it with crafts and paints and sports and friends.

And even now, despite her memory loss, when she says something snarky about my hair or makes a rude comment about someone down the hall, I say to myself, “There she is,” and I smile. She’s in there, this woman who raised me. A spark of spitfire still flickers. My mom.